In an attempt to focus blogging activity to more in depth, considered essays, I have started a new blog called The Aporia of the Dual Perspective, the address is here: http://markpeterwest.blogspot.com

The blog's title comes from Peter Osbourne's book The Politics of Time: Modernity and Avant-Garde, and refers directly to Paul Ricoeur's attempts to consider both the experience of lived time and that of "cosmic" time. I've been reading Osbourne's book recently for my PhD, and have found Ricoeur - as summarised by Osbourne - fascinating. Not only is this aporia an accurate description of time, but it resonated with me further: the dual perspective can be that of contradicting stories, narratives, actions, events, of inward and outward, of self and other. It seems to me that I'm dealing with this aporia in various ways most of the time.

Essential Skills

25.3.12

28.1.12

A Film Is A Statement

1. We must make political films.

2. We must make films politically.

32. To carry out 2 is to dare to know where one is, and where one has come from, to know one's place in the process of production in order then to change it.

The opening performance of Arika's recent weekend of film was by the Museum of Non-Participation and is probably best described as being immersed in a physical documentary. It noted simultaneously the audience’s active position and that audience's sort of belated insufficiency as actor. That is to say, the audience is never quite there. The work was arranged throughout a large studio space with numerous screens onto which separate images (both moving and still) were projected while the artists performed a pre-prepared text that alotted them each "parts" which they read in turn.

If it is true to say that the space of the work and the space of the audience were collapsed, with the latter contributing through its movement around the room, choosing which simultaneous projection to focus on, walking on the same level as the artists who mingled in and out of audience members while reading, then it is also true that through this very device an amplification of film's relation to distance was effected. At a basic level film shows you something, and by implication the thing being shown remains to some degree outside of, distinct from, oneself. Here, this distance was strangely augmented by pushing the audience toward a greater blend with the work. In so-doing, the work amplified an existing tension: a screen's manifestation of separation. This contradiction is present in the word "screen" itself: it is something onto which something can be projected and thus shown, but it can also screen off something, making it unable to be seen. The work manifested this tension even as images poured over and beyond the screens, and as different images projected on different screens at the same time, requiring an audience selection of priorities. In its attempts to disrupt that singular experience of one person watching one screen, it recalled it even more.

Space is clearly important. Is critical thought best served through immersion or through a clear demarcation of thinker and that-which-is-to-be-thought-about? In a way the work turned on this question, mentally pacing it out, embodying an ambivalent answer. At one point, the artists noted the discombobulating experience of watching a lawyers protest against Musharaf in Pakistan in 2007 from the white space of a contemporary art gallery. As a metaphor for the spatial dynamic the work itself was acting out, it was a simplified one. The work’s effectiveness came from its very complication – and making-extreme-of – that inside/outside binary.

Sound is equally important. That which came from the various projections and the artists' reading was akin to that of a documentary (the projections slightly quieter than the voices "over the top"), but a moment where the street sounds of a Pakistani protest triumphed over the shuffling of audience feet and murmur marked a point of intense immersion. It resembled a piece by Chris DeLaurenti, performed at Instal in November 2010, N30: Live at the WTO, which turned the pitchblack gigantic space of Glasgow's Tramway 1 into a simultaneously aural memorial and re-enactment of the World Trade Organization protests of 1999. It was beautiful, angering and above all deeply moving.

So far I've focused on the audience watching. In “The Tracking Shot in Kapo,” Serge Daney describes Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour as ‘“things” that have watched me more than I have seen them.’ A text pointed to by Arika as a point of departure for the weekend, in this context it asks: What are the variations of non-participation? We can not participate in an oppressive society. Either by sheer refusal or by active participation in oppositional organization. We can not participate in the struggles of resistance (of the forming of oppositional organization). Either because of doubts and fears, or by compromise, by the complications that make binaries problems in the first place. Daney’s switch gives it another meaning: accusative, it demands a reason for one’s actions, for participation or non-participation. It is a demand for active thought.

What is true about the Museum of Non-Participation is that the audience participates in its work. But what is that work? It seems to be the manifestation of an argument (like the film Argument, shown on Saturday): complications and complexity exist (in the pouring, the multiplicity, the simultaneity of images), but binaries (choice) will continue to exist. How does one remain faithful to both of those realities?

But I haven't put this quite right. It aligns the inescapable boundary the screen creates with the choice of one-or-the-other. It aligns the inescapable complexity of the world with an overflowing of images. The problem is this: that boundary stops action, whereas the choice of one-or-the-other creates action: one chooses and one follows that choice. With the boundary one never has to choose because one is always stuck this side of it. What would be better to say would be that somehow the immersion – through the overflowing of images, the simultaneity of them – demands a choice. Perhaps the immersive tendencies of this Museum are a way of dragging one in off the fence, and the abrupt meeting with the screen a metaphor for the accusative demand. Through immersion one is being dragged into the struggle (one of art, of politics, and art-and-politics) and one's position then has to be defended, thought about.

Lutz Becker's film Kino Beleske (Film Notes), screened immediately after The Museum of Non-Participation, was a document of the Student's Cultural Centre in Belgrade in 1975. Throughout, various members speak pieces to camera which reminded me a lot of La Chinoise, which surely figured somewhere in the weekend's thinking if not Becker's. At one point a Serbian student appears wearing sunglasses covered in tin foil, echoing Jean-Pierre Léaud's nationalist glasses in Godard's 1967 film.

During these pieces to camera one hears the cars, horns, wind on the streets outside which continued being streets as the artists spoke. It seemed to me that the effect of this - desired or otherwise - was to dramatize the same question of the position of critique that the Museum of Non-Participation did. (What does it mean to participate? What is one participating in? Is non-participation a form of participation in another activity? Is there such a thing as not doing anything?) What was the relation of these students now speaking to camera and those streets we can hear? Watching the film over thirty years later, the students' relation is more that to contemporary art (especially given the appearance of artists that would go on to make big names for themselves) than their immediate surroundings. There is a risk that those streets get lost in a dialogue that focuses on career patterns or the amused comment of a friend seeing a younger incarnation of a newer acquaintance. The film's soundtrack kept that risk from being trampled, and forced one to consider one's position in relation to the film, the film's in relation to the audience, the situation of us watching it to the film's history, to art and political history, to ongoing narratives.

Chto Delat?'s songspiels understood position as movement. In “What Does It Mean To Make Films Politically?” one of the group’s members, Dimitry Vilensky, writes: “political cinema is a multi-layered composition that combines emotional effects and total intellectual analysis. Paradoxically, we must learn to touch the viewer’s heart without entertaining him.” Needless to say, the entertainment evoked here is the particularly seductive kind of Hollywood and mass culture.

In a phone-call to the audience before the screening, though, Dimitry talked about wanting the work to be entertaining. What could he have meant? I think he meant it to be mobile: their films are available on their website and Dimitry talked about them being screened in different countries and contexts. Certainly the form - though recognizably Brechtian, with a particular history - is not too far removed from certain popular entertainments. The closest thing in a British context might be music hall, except with the politics evacuated and replaced with a certain type of cynical bawdiness. (As I began writing this, in fact, I noticed a review of a new musical called Big Society).

Discussions of avant-garde artistic practice are understandably wary of terms like "entertainment" and "popularity", but I do think it is an important question to ask. How does avant-garde art understand its relation to mass culture? Godard's "What Is To Be Done?" is useful here. To make political films or to make films politically represent two understandings of this relation. Godard is explicit about this: one represents a certain - yet limited - step forward; the second represents a deeper commitment.

This isn't about co-option but ambush. Surprisingly enough, given assumptions of the historical avant-garde's contemporary uselessness, the form of the songspiel Chto Delat? use creates a new twist on artistic history: it inaugurates a direct link between contemporary art and its antecedents that is a link of continuation and development (a positive tradition) rather than nostalgia-tinged analyses.

Yet there is also something less direct about this mobility, and it points to an interesting idea: that often politcally active art achieves results by circuitous routes, by accident rather than as a direct answer to the question What Is To Be Done? In this alternative understanding of effect, art can use surprise (ambush) as a tactic, but only really if it is unaware of doing so. We wait years for revolution and then numerous ones pop up in countries we'd never have expected (although perhaps we weren't looking closely enough).

2. We must make films politically.

32. To carry out 2 is to dare to know where one is, and where one has come from, to know one's place in the process of production in order then to change it.

The opening performance of Arika's recent weekend of film was by the Museum of Non-Participation and is probably best described as being immersed in a physical documentary. It noted simultaneously the audience’s active position and that audience's sort of belated insufficiency as actor. That is to say, the audience is never quite there. The work was arranged throughout a large studio space with numerous screens onto which separate images (both moving and still) were projected while the artists performed a pre-prepared text that alotted them each "parts" which they read in turn.

If it is true to say that the space of the work and the space of the audience were collapsed, with the latter contributing through its movement around the room, choosing which simultaneous projection to focus on, walking on the same level as the artists who mingled in and out of audience members while reading, then it is also true that through this very device an amplification of film's relation to distance was effected. At a basic level film shows you something, and by implication the thing being shown remains to some degree outside of, distinct from, oneself. Here, this distance was strangely augmented by pushing the audience toward a greater blend with the work. In so-doing, the work amplified an existing tension: a screen's manifestation of separation. This contradiction is present in the word "screen" itself: it is something onto which something can be projected and thus shown, but it can also screen off something, making it unable to be seen. The work manifested this tension even as images poured over and beyond the screens, and as different images projected on different screens at the same time, requiring an audience selection of priorities. In its attempts to disrupt that singular experience of one person watching one screen, it recalled it even more.

Space is clearly important. Is critical thought best served through immersion or through a clear demarcation of thinker and that-which-is-to-be-thought-about? In a way the work turned on this question, mentally pacing it out, embodying an ambivalent answer. At one point, the artists noted the discombobulating experience of watching a lawyers protest against Musharaf in Pakistan in 2007 from the white space of a contemporary art gallery. As a metaphor for the spatial dynamic the work itself was acting out, it was a simplified one. The work’s effectiveness came from its very complication – and making-extreme-of – that inside/outside binary.

Sound is equally important. That which came from the various projections and the artists' reading was akin to that of a documentary (the projections slightly quieter than the voices "over the top"), but a moment where the street sounds of a Pakistani protest triumphed over the shuffling of audience feet and murmur marked a point of intense immersion. It resembled a piece by Chris DeLaurenti, performed at Instal in November 2010, N30: Live at the WTO, which turned the pitchblack gigantic space of Glasgow's Tramway 1 into a simultaneously aural memorial and re-enactment of the World Trade Organization protests of 1999. It was beautiful, angering and above all deeply moving.

So far I've focused on the audience watching. In “The Tracking Shot in Kapo,” Serge Daney describes Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour as ‘“things” that have watched me more than I have seen them.’ A text pointed to by Arika as a point of departure for the weekend, in this context it asks: What are the variations of non-participation? We can not participate in an oppressive society. Either by sheer refusal or by active participation in oppositional organization. We can not participate in the struggles of resistance (of the forming of oppositional organization). Either because of doubts and fears, or by compromise, by the complications that make binaries problems in the first place. Daney’s switch gives it another meaning: accusative, it demands a reason for one’s actions, for participation or non-participation. It is a demand for active thought.

What is true about the Museum of Non-Participation is that the audience participates in its work. But what is that work? It seems to be the manifestation of an argument (like the film Argument, shown on Saturday): complications and complexity exist (in the pouring, the multiplicity, the simultaneity of images), but binaries (choice) will continue to exist. How does one remain faithful to both of those realities?

But I haven't put this quite right. It aligns the inescapable boundary the screen creates with the choice of one-or-the-other. It aligns the inescapable complexity of the world with an overflowing of images. The problem is this: that boundary stops action, whereas the choice of one-or-the-other creates action: one chooses and one follows that choice. With the boundary one never has to choose because one is always stuck this side of it. What would be better to say would be that somehow the immersion – through the overflowing of images, the simultaneity of them – demands a choice. Perhaps the immersive tendencies of this Museum are a way of dragging one in off the fence, and the abrupt meeting with the screen a metaphor for the accusative demand. Through immersion one is being dragged into the struggle (one of art, of politics, and art-and-politics) and one's position then has to be defended, thought about.

Lutz Becker's film Kino Beleske (Film Notes), screened immediately after The Museum of Non-Participation, was a document of the Student's Cultural Centre in Belgrade in 1975. Throughout, various members speak pieces to camera which reminded me a lot of La Chinoise, which surely figured somewhere in the weekend's thinking if not Becker's. At one point a Serbian student appears wearing sunglasses covered in tin foil, echoing Jean-Pierre Léaud's nationalist glasses in Godard's 1967 film.

During these pieces to camera one hears the cars, horns, wind on the streets outside which continued being streets as the artists spoke. It seemed to me that the effect of this - desired or otherwise - was to dramatize the same question of the position of critique that the Museum of Non-Participation did. (What does it mean to participate? What is one participating in? Is non-participation a form of participation in another activity? Is there such a thing as not doing anything?) What was the relation of these students now speaking to camera and those streets we can hear? Watching the film over thirty years later, the students' relation is more that to contemporary art (especially given the appearance of artists that would go on to make big names for themselves) than their immediate surroundings. There is a risk that those streets get lost in a dialogue that focuses on career patterns or the amused comment of a friend seeing a younger incarnation of a newer acquaintance. The film's soundtrack kept that risk from being trampled, and forced one to consider one's position in relation to the film, the film's in relation to the audience, the situation of us watching it to the film's history, to art and political history, to ongoing narratives.

Chto Delat?'s songspiels understood position as movement. In “What Does It Mean To Make Films Politically?” one of the group’s members, Dimitry Vilensky, writes: “political cinema is a multi-layered composition that combines emotional effects and total intellectual analysis. Paradoxically, we must learn to touch the viewer’s heart without entertaining him.” Needless to say, the entertainment evoked here is the particularly seductive kind of Hollywood and mass culture.

In a phone-call to the audience before the screening, though, Dimitry talked about wanting the work to be entertaining. What could he have meant? I think he meant it to be mobile: their films are available on their website and Dimitry talked about them being screened in different countries and contexts. Certainly the form - though recognizably Brechtian, with a particular history - is not too far removed from certain popular entertainments. The closest thing in a British context might be music hall, except with the politics evacuated and replaced with a certain type of cynical bawdiness. (As I began writing this, in fact, I noticed a review of a new musical called Big Society).

Discussions of avant-garde artistic practice are understandably wary of terms like "entertainment" and "popularity", but I do think it is an important question to ask. How does avant-garde art understand its relation to mass culture? Godard's "What Is To Be Done?" is useful here. To make political films or to make films politically represent two understandings of this relation. Godard is explicit about this: one represents a certain - yet limited - step forward; the second represents a deeper commitment.

This isn't about co-option but ambush. Surprisingly enough, given assumptions of the historical avant-garde's contemporary uselessness, the form of the songspiel Chto Delat? use creates a new twist on artistic history: it inaugurates a direct link between contemporary art and its antecedents that is a link of continuation and development (a positive tradition) rather than nostalgia-tinged analyses.

Yet there is also something less direct about this mobility, and it points to an interesting idea: that often politcally active art achieves results by circuitous routes, by accident rather than as a direct answer to the question What Is To Be Done? In this alternative understanding of effect, art can use surprise (ambush) as a tactic, but only really if it is unaware of doing so. We wait years for revolution and then numerous ones pop up in countries we'd never have expected (although perhaps we weren't looking closely enough).

10.8.11

A letter to Rebecca Solnit about following in footsteps, unwittingly

Dear Rebecca,

I'm not quite sure whether to apologise for writing. It feels vaguely, generically risky, as if I'm crossing a line I don't know about but everyone else is watching in horror as I stride obliviously over it.

I am writing because I am having one of those extended epiphanic periods of discovery with a writer, where you read book after book, interview after interview, out of sheer excitement, and at some point you actually feel your understanding of the world shifting a little, widening out, dots meeting with other dots, everything becoming clearer yet also simultaneously - and frustratingly - cloudier: do I have so much still to learn? This writer, if you haven't guessed, is you, the books and interviews yours, and I'm writing because it felt natural to express this experience one way or another. Strange though to think that this letter is one that will be read by more than one person but the single person to whom it's addressed may never read it.

I had been meaning to read your work for quite a while. I started with A Field Guide To Getting Lost, which I started in July this year. I loved it, read it quickly, and moved on toSavage Dreams: A Journey into the Landscape Wars of the American West, which I thought equally remarkable. Somewhere between finishing the former and starting the latter, I finally confirmed that I was going to be returning to San Francisco for the first time since 2008, this time for my friend Tobias's wedding. It had been stressful, and worrying, and saddening, thinking I couldn't go (Tobias had asked me to be one of his groomsmen), and a weight lifted, and all the mentions of that great city in your work became less abstract, less faraway fairytale and more a place that had direct relevance to me.

I have to confess, though, that once I arrived in San Francisco, I hardly read your book. I was only 100 pages or so from the end of Savage Dreams, and looking forward to starting Wanderlust: A History of Walking (I love that heavily emphasised "a", so importantly destabilising), but the city took over, and I hardly read a word - of anything - for 10 days. Reading suddenly seemed neglectful of this place, this glinting, grimy peninsula right there outside our window. Maybe travelling is less a time for contemplation than wholesale immersion; I continued writing in my journal for the first few days, then slumped into writing bullet-pointed lists of the main events and stops of the day, then stopped even that.

I did buy your Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas in City Lights. Carrying it around for a day before getting home, I wondered about using it literally, taking out the maps and following the routes, reading the essays whilst walking. But the book seems less direct than that. The "infinite" does it: the variations, the endless reconceptualisations of a city are dreams of a place that only half exists, the rest made from the tumbling process of linking experience and imagination and history to that first half, the firm sediments of streets, buildings, and people.

Perhaps I lied a bit about not reading, but your atlas was the only thing I spent any real reading time with, reading late in the evenings, sitting with the window open and hearing the nightly shouts and laughs and sirens of the Tenderloin. This worked just as well, the small essays about a neighbourhood we'd either been to that day or the day before, or were planning on going to the next, seeping into my knowledge of those places, adding and layering and complicating the city. (It's hard to write about it with the right amount of distance, now, back in Glasgow, on a day of rain. That city? This city? The city? Is the distance psychological or geographical? Miles and hours don't seem enough to describe the distance, both nearer than them and much farther). I read about the gangs of the Mission, realised I'd walked through the site of a murder, oblivious, searching for ice cream. I read about Muybridge and Hitchcock's own weaving footsteps, 50 years apart, knowing about the latter but nothing about the former, save his famous pictures. Your unlayering of the complicated politics of Civic Center and UN Plaza: the UN formed there?! Really? And the right-wing intelligentsia stationed in think tanks and laboratories surrounding the city, the wider Bay Area turned into a pincer clutching liberal San Fran with its "real America" hawkism.

***

Returning from my own wanderings, I finally started Wanderlust. In it, you write about the connection between walking and writing:

"Just as writing allows one to read the words of someone who is absent, so roads make it possible to trace the route of the absent. Roads are a record of those who have gone before, and to follow them is to follow people who are no longer there."

Reading your words whilst walking in your city, these two practices, similar but separate, merged in a complicated way: reading your words allowed me to trace on a road your absent footsteps. Although it wasn't about you, really; not then, anyway. It was about the city and its history, and we were just two of the millions of human beings that have been part of that history, however small our roles. My relationship was not with you but with the city, just as yours was not with me but with the city. We were two people brought into connection by the city, and the revelation at first was that it was possible for two people to have similar reactions to a place. It was like that moment where you realise that a piece of music you have had such an intimate relationship with that it seems it exists only for you actually exists for the rest of the world too, and people have entirely differently intimate relationships with it, but also, sometimes, have almost exactly the same intimate relationship with it.

I'm not sure that's very clear. I'm struggling to pinpoint the angles of the relationship. What I'm trying to say is that I walked around your city, and halfway through that wandering I bought and read some of your words, which then influenced how I experienced and interpreted that city. So perhaps they could have been anyone's words, any words. I could have read a straight history of San Francisco and had a similar, albeit slightly different, experience. I would have been subject to another interpretation of the city, with all the prejudices, interests, and political biases that involves. But the point is I did read your words, not someone else's.

***

But there was a point, only when I got home, only when I was looking at the photographs I had taken of the city and I was separated from the immersive visual experience of it, that I fully realised what was happening. Somewhere and sometime the relationship changed; when I paused my reading of Savage Dreams because of the overwhelming "being-right-there" of the city itself, I changed the dynamic from one of conscious knowledge of your footsteps to total ignorance. My connection to you was cut off, because I stopped reading your words.

On the torturously long flight over, when I was too tired to read your book and it sat in my lap like some sort of totem, we passed over the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah and past Elko and Winnemucca in Nevada, almost over Yosemite, the places you explore in Savage Dreams. I knew what the Salt Flats were because of your book! But that's when it stopped. For the next ten days, your influence fluttered and crackled like a radio, but the signal was never direct. It's true we went to the Tenderloin National Forest because of what you write about it in Infinite City, "a lush refuge in a rough neighbourhood":

But I had no idea I was unwittingly following in your footsteps when I went to the same bar you write about in Wanderlust:

"I had a date to meet some friends for drinks at the famously kitschy old mock-Polynesian bar the Tonga Room in the Fairmont Hotel atop Nob Hill."

Here is my film of the band on the boat on the pool in the bar:

Nor indeed when I wandered around the Grace Cathedral and watched two elderly Chinese ladies exercising by the labyrinth:

"In pale and dark cement it repeated the same pattern made of stone in Chartres Cathedral: eleven concentric circles divided into quadrants through which the path winds until it ends at the six-petaled flower of the center."

You can just see a bit of the labyrinth at the bottom of the photo I think.

And I had somehow missed all these places you write about in Infinite City, like Dolores Park, where we dozed before going to see a terrible film at the Roxie Theater (which you note in your sad map of the demise of local movie theaters):

Three years after I first tried going (we were too late; it was closed) I saw the graveyard of the Mission Dolores. I knew I was following in Hitchcock's, Kim Novak's and James Stewart's footsteps, but not yours:

So many of "the forty-nine jewels of San Francisco" you've wandered before us. The Women's Building, which we went to in 2008:

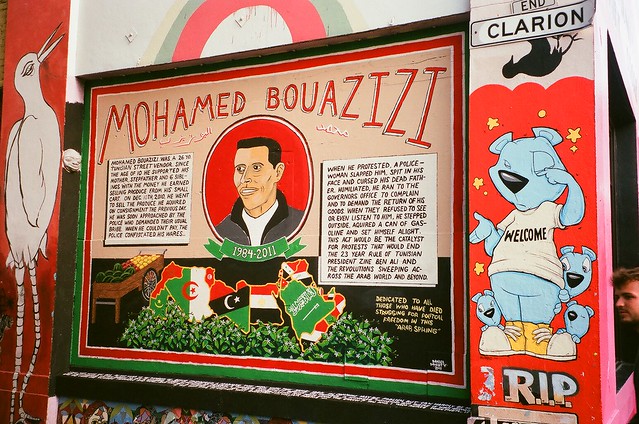

This year the murals we saw were in Clarion Alley, your "carnival of visions":

The "fairytale palace" Conservatory of Flowers, where we went for a reading and watched an exotic beetle on the floor:

The Castro Theatre, in the midst of the Jewish Film Festival:

And in the atlas you too go to Sugar Café, Dottie's True Blue Café, Mission Pie, Four Barrel...

***

And then somewhere it flipped; I was no longer following you, you were following me.

When we arrived home, exhausted from the 13 hour flight and a 6 hour train journey from London, slumping onto the sofa, in front of me on the coffee table was a book entitled English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages, by one J.J. Jusserand, the same book and author I presume that Christopher Morley is referring to in the section you quote in Wanderlust:

"We know from Ambassador Jussurand's famous book how many wayfarers were abroad on the roads in the Fourteenth Century..."

My first weekend back at work in Kelvingrove Art Gallery, I served an American lady who when she turned away from the counter was revealed to be wearing a black backpack with a Sierra Club badge on it, the same name of the club that you write about in Savage Dreams, one of America's oldest environmental groups, founded by John Muir, who was born in Scotland.

***

I've had to slow down my reading of Wanderlust because I am wandering again in a few weeks time, this time less aimlessly, to Antwerp to give a paper at a conference. I will be talking about abiding, and David Foster Wallace, and American politics, and I suspect you will pop up in there somewhere, a now-abiding presence in my life and whose political activity and its relationship to your wonderful writing I have hardly touched on here, if only because it poses so many questions I will have to think about it for a long time before I write anything about it.

I am happy that you are a prolific writer, that I not only have lots more of your books to read but that I will probably read them again and again for their beautiful complexity and acute, intuitive understanding of one's relationship to place, literature and history.

Your ongoing reader,

Mark

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Me

- Mark

- I am writing a PhD at the University of Glasgow entitled "The Poetics of Time in Contemporary Literature". My writing has been published in Type Review, Dancehall, Puffin Review and TheState. I review books for Gutter and The List. I am also an editor and reviewer at the Glasgow Review of Books.